Chapter 9: History

The 2012 Australian Open final pitted Djokovic's tactical dominance against Nadal's unbreakable will. The product? A historically attritional major final.

“Rafa! Rafa!”

Rafael Nadal walked in a circle by the baseline, gritting his teeth and pumping his left fist. He’d spent the previous two and a half hours getting the brakes beaten off him by Novak Djokovic. Though the third set of the 2011 U.S. Open final indicated that Nadal could be competitive with Djokovic at his best, Djokovic’s play in the previous hour established a new frontier. Nadal looked as lost as he ever had in a thoroughly one-sided 6-2 third set. But down 3-4 and love-40 in the must-win fourth, Nadal had produced a miraculous hold of serve: two winners from the baseline, three unreturnable serves. Four hours in, the match felt at its most alive yet. The set and a half to follow would hit peaks until there were no summits left to climb.

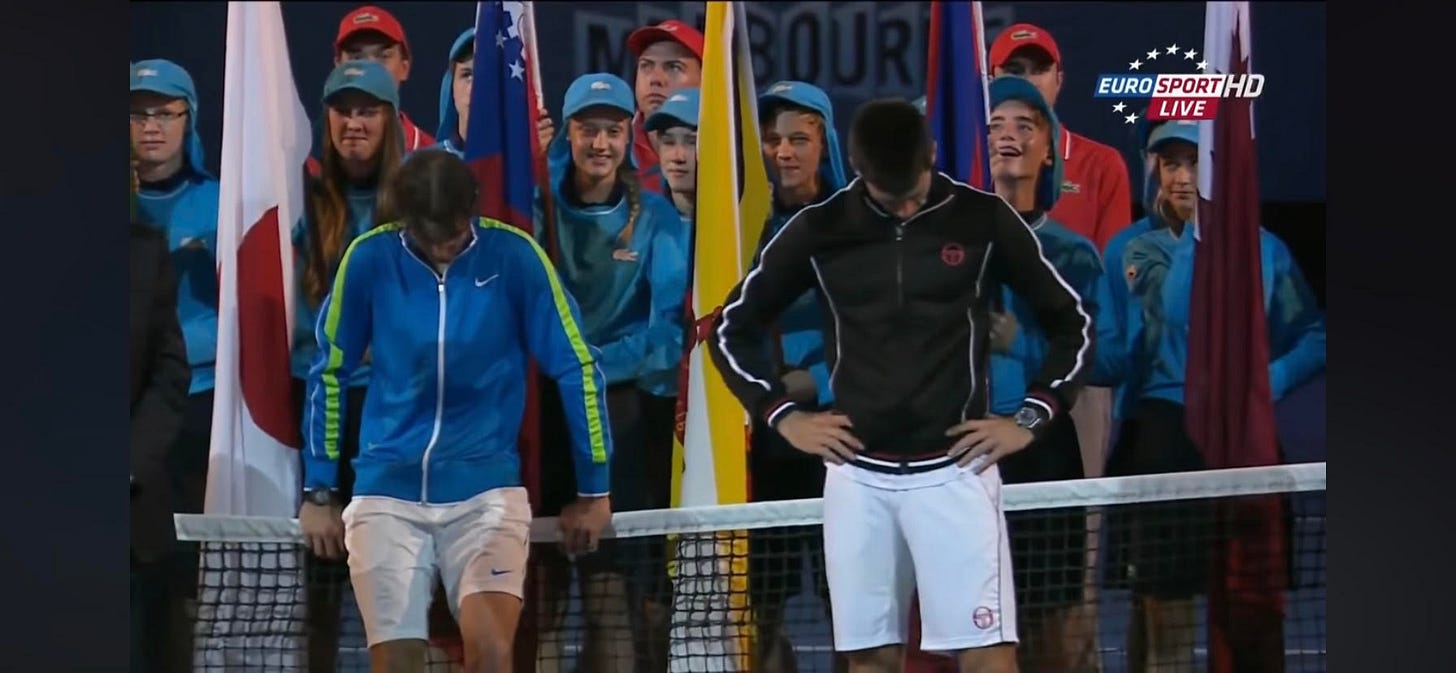

“These are the two guys now,” ESPN broadcaster Chris Fowler said as Djokovic and Nadal stood in the tunnel before the match. “After today, they will have shared the last eight Grand Slam titles.” That may have been so, the Djokovic-Nadal rivalry taking over from Nadal-Federer, but Djokovic was unquestionably in the ascendancy. He had won their last six matches, their last two major finals. What made the 2012 Australian Open final potentially different, at least prior to the match, was that Djokovic had endured a brutal route to the championship match, looking physically vulnerable in his previous three wins.

The “Big Four,” the quartet of Djokovic, Nadal, Federer, and Murray, had been established for a while. But the 2012 Australian Open may have been their finest hour as a group. While Djokovic and Nadal were the two standouts of the foursome at the time, Murray and Federer made fierce stands against them.

Djokovic had the misfortune of meeting Murray on one of his best days in the second semifinal. The court was playing as slow as molasses, which was a death trap for players as balanced as Djokovic and Murray. Murray was in the same mold as Djokovic, with clean, consistent groundstrokes, elite defense, and at times, a bit of a power deficit. Almost immediately, the rallies stretched to insane lengths. One late in the second set went 43 shots. Djokovic started to visibly struggle physically before the second set had even ended. The first phase of the match culminated in an epic third set which Djokovic pushed to a tiebreak despite twice being down a break. He had appeared to be on the back foot for most of the time, but kept the set close through well-timed bursts and force of will. Murray won the set anyway, which felt like an incredibly meaningful blow.

After Murray won the third set, a commentator said that his lead felt more like two and a half sets to one than two sets to one. But Djokovic timed a push brilliantly in the fourth set just as Murray had a physical letdown, winning the fourth set 6-1. At game point for 5-1, Murray got yanked wide on his forehand side and smacked a go-for-broke shot as hard as he could. Djokovic slid into the reply, his forehand stroke describing a perfect semicircle in the air, looping a winner down the line. Murray came back hard at Djokovic in the fifth. With the Serb serving at 5-all, Murray had three break points, one of which Djokovic saved by hitting a stunning forehand down the line at the end of an insane 29-shot rally. After escaping with the hold (and celebrating thunderously), Djokovic coolly broke serve in the next game to seal the match.

Djokovic fell to the ground after match point as if the semifinal had been a final. The match had taken four hours and 50 minutes. It was only marginally less dramatic than his five-set comeback over Federer at the U.S. Open months earlier, and it had been far more physically taxing. For all Djokovic’s tactical, physical, and mental holds that the Serb had earned over Nadal in 2011, going into the final, many had the Spaniard as the favorite.

Not that Nadal hadn’t had his own challenges. He had the most difficult quarterfinal of anyone, clashing with a red-hot Tomáš Berdych. He lost the first set in a tiebreak and faced a set point in the second set but squeaked through to tie the match. From there, he was irresistible—he played as aggressively as possible and was near the peak of his powers defensively. After the second set, he proceeded to rain down hot shot winners on Berdych for the rest of the match: return winners, passing shots hit at full stretch, forehand blasts from the baseline. Berdych was still playing well, very well, but he was up against a raging storm. Nadal sealed the match with a forehand return down the line that Berdych could barely touch, emblematically breaking at love. The match had lasted for an exhilarating four hours, but Nadal’s razor-sharp form towards the end of the quarterfinal more than made up for any physical deficit he might have been at afterwards.

In the semifinals it was Federer, who was actually favored to beat Nadal—as Djokovic faded down the stretch in 2011, Federer surged, winning Paris and the World Tour Finals. In the latter, he’d demolished Nadal 6-3, 6-0 in the group stage. At first, it looked as if Federer was implementing Djokovic’s tactics from 2011 to good success—he was using his forehand to keep Nadal pinned in the backhand corner, then only attacking the open court when he was positive there was enough space to do so. That in conjunction with some incredible aggression from the backhand guided Federer to a 7-6, 1-0 lead.

It didn’t last—Nadal cranked up the pressure and Federer deviated from his disciplined gameplan, approaching the net more and more. Nadal responded with stunning passing shots, several of which were hit from scarcely believable positions. Late in the fourth set, Federer crushed a punishing forehand down the line, hit with such pace and precision that the Swiss momentarily stopped playing. When Nadal got it back at the very edge of a shrieking sprint, Federer had to quickly snap back to attention, running up to net for the putaway. The eventual scoreline of 6-7 (5), 6-2, 7-6 (5), 6-4 reflected the close-but-clear win for Nadal.

So the final was set: Federer and Murray were huge challengers, more than live underdogs, but Djokovic and Nadal were ever so slightly superior. The entirety of 2011 indicated that Djokovic was a solid favorite, but he had looked dead on his feet in patches against Murray, and the semifinal looked to have taken its toll in the first set against Rafa. As Nadal held easily, Djokovic sprayed inside-out forehands wide and long. When Novak did execute well, Nadal outdid him. With Djokovic serving at 2-all, deuce in the first set, he approached the net behind a solid inside-in forehand. Nadal’s backhand pass zipped right at Djokovic’s racket and the Serb punched a volley deep to the forehand side.

That should’ve been the end of the point. Commentators on various feeds admitted to thinking it was. Nadal disagreed. He ran like hell for the ball, then flapped his racket at it with his huge left arm, somehow getting enough power on the stretch to get the fluffy yellow thing over the top of the net. Presented with an awkward short ball, Djokovic flicked a slow backhand down the line. Given a chance at the same backhand pass he had failed to execute two shots earlier, Nadal coolly rolled the winner crosscourt past a stock-still Djokovic at net.

Even with Nadal sharp and Djokovic error-prone, though, the set was a slog. Nadal broke for 3-2 after countless deuces, then held for 4-2 after countless more. Djokovic broke back for 4-4 after another long game. At last, Nadal called up a huge crosscourt backhand and a forehand down the line to break at 5-all, then survived yet another deuce game to win the opener 7-5—in 80 minutes.

While this seemed ideal for Nadal—he’d put another hour-plus on Djokovic’s weary legs and had a lead, to boot—keen observers saw a different story. Djokovic had hit 19 unforced errors in the first set and made only 51% of his first serves (to Nadal’s 76%), yet the set required a huge effort from Nadal to win. In 2022, I reviewed the match with Vallejo on the Tennis and Bagels podcast. At my request, Vallejo sent me his notes after the episode, and his line describing the end of the first set may have been the most striking: “Set to Nadal, 7-5. The steadier player, but you can see it in his eyes that he has no answer for Djokovic if the good stuff comes.”

Djokovic’s aforementioned A game wasn’t long in coming. It started with his return of serve. Nadal was serving bigger than he had in the U.S. Open final months before, where he was content to spin in many of his first serves at barely 100 mph, but here in Melbourne Djokovic was totally unbothered by the extra zip. He started firing deep returns that rushed Nadal or angled shots that forced Rafa onto the run, and from there, Djokovic would blast away until the wall on the other side of the net cracked.

It sounds simple, but the gameplan required an absurdly high level of execution. Nadal’s forehand was so dangerous if given a moment to wind up; each and every one of Djokovic’s crosscourt backhands and inside-out forehands needed to have venom on it to keep Nadal defending desperately by the MELBOURNE letters painted well behind the baseline on the sea-blue court.

More often than not, they did. Djokovic rapidly took control of the match in the second set. His returns started to torch the baseline. His groundstrokes gradually increased in pace and depth, depriving Nadal of time and allowing Djokovic to take over rallies with his forehand. He directed traffic to Nadal’s backhand, which started to misfire or drop short. Down 5-3 in the second set, Nadal blasted a couple forehands down the line en route to retrieving a break deficit he had faced all set, but Djokovic hit back in the very next game with a series of devastating returns, forcing error after error. Feeling the pinch, Nadal double faulted on set point to even the match. Vallejo told me on Tennis and Bagels that it seemed like Djokovic had decided to get the break back simply because he could, such were the devastating capabilities of his return of serve.

The third set was the culmination of Djokovic’s six straight wins over Nadal, of a year of tactical dominance. He simply dissected Nadal’s game as an expert surgeon would conduct a hurried autopsy. The extent of Djokovic’s supremacy is best shown through stats: He lost just two points on serve in the third set. Nadal’s incredible forehand was only allowed enough time to deliver one winner. Djokovic broke serve twice, once at love. He wrapped up the set by winning eight points in a row. Djokovic’s game to break for the set at 5-2 is just nuts, Vallejo’s note read. Emphatic swaggering domination.

For all it seemed Nadal had awakened some new self-belief by winning the epic tiebreak set against Djokovic in the U.S. Open final, the third set in Melbourne erased it. Nadal’s game, the same game with which he had beaten Federer on all three surfaces and that had won him 10 major titles, had been dismantled. He was laid bare on Rod Laver Arena. Gill Gross of Monday Match Analysis reviewed this final on his channel in May of 2020 and commented specifically on this portion of the match. “95 to 98 percent of players would have quit [after the third set],” he said. “That’s the truth. That’s how well Djokovic was playing. If Djokovic plays that well against 95 to 98 percent of players, the other player quits. They go away. That’s the match. They give up. They’re demoralized.”

Imagine how Nadal must have been feeling. He was way behind. The man on the other side of the net was not only as complete a player as had ever played tennis, but had a game that was poison for Nadal specifically. Djokovic was hitting his own shots at an incredibly high level and denying Nadal the opportunity to do the same thing. Rafa’s game looked almost totally ineffectual at times; even points on his own serve began with Djokovic hitting deep, then pushing him from side to side until the inevitable winner. Djokovic felt so comfortable from the baseline that even Nadal’s superb defense wasn’t doing that much. As long as he kept depriving Nadal of time, he was safe and didn’t need to aim for tiny targets. By comparison, Nadal was looking at someone who defended as well as him and was better at timing the ball when it came at him hard and deep. Oh, and Nadal had spent the entire previous season trying and failing to beat Djokovic.

Think it’s easy to make a comeback from that position?

There was one option open to the Spaniard, and it was a dangerous one. He could stand on the baseline, refuse to be pushed back, and blast blazing groundstrokes. He could ignore the fact that he was at his best when given time and try to produce the same shot quality when rushed. It was a scary possibility—this wasn’t Nadal’s game, at all. He was offensive-minded but wasn’t that accustomed to attacking from neutral or defensive positions rather than comfortable ones. Yet here, there was no other choice. Nadal had to jump.

And he did.

Right from the start of the fourth set, in fact. Djokovic served first, and the first point of the set was a Djokovic unforced error—nothing remarkable—but Nadal immediately roared a “VAMOS” that could have shattered glass. At love-15, Nadal maneuvered himself into the rare position of being able to unload on a few forehands, blasting them inside-out time and again. Despite being put on the defensive, Djokovic’s forehand held firm. He got one back deep that forced Nadal to cough up a short ball. The Serb cracked an angled backhand crosscourt, which Nadal, going for broke, ripped down the line. On the dead run, Djokovic scooped a marvelous angled crosscourt forehand into the opposite corner, pulling Nadal so far off the court that it easily opened up space for a drop shot. Nadal ran like hell but couldn’t get to the ball. It was a demoralizing point; Nadal had for once been able to boss a rally, but Djokovic’s defense denied him. A lesser player might have accepted that it wasn’t their day, that Djokovic was inevitable, but Nadal maintained his intensity. While Djokovic eventually held serve in that first game, Nadal got in a couple deep first serve returns and hung tight to the baseline, ensuring he’d be able to attack at the soonest opportunity. Djokovic had to work for a hold of serve for the first time in a while.

Djokovic in turn pressured Nadal’s serve in the following game, but the dynamic of the match was already shifting. Nadal was pasting backhands instead of looping them, and now the shot quality was equal on both sides of the net. His more aggressive gameplan was resulting in some errors, but when he kept the ball inside the lines, the rallies were dead even, whereas before Djokovic was running Nadal ragged constantly. When the Spaniard banged an ace to hold for 1-all, his celebratory “sí!” felt more meaningful than his futile resistance in the third set.

The fact remained that Djokovic was in searing form. Returning up 4-3, he dropped a backhand winner onto the line, forced Nadal into bad court position with a defensive slice, then pulverized a forehand winner down the line to go up love-40.

Yet Nadal survived that too. The set went to a tiebreak, just like the third set of their 2011 U.S. Open final. Through it all, Nadal had continued to run down every ball he could, and towards the end of the set, you could see Djokovic starting to tire a bit. The Serb tried his best to kill off the match in the tiebreak. He got close—he went up 5-3 with an enormous forehand winner. But Nadal’s defense finally started to pay dividends, scraping balls back into play time after time, and finally Djokovic’s forehand imploded, making three errors in the final four points of the tiebreak. When Djokovic sailed a last forehand wide down set point, Nadal dropped to his knees in pure ecstasy.

While the set hadn’t featured many rallies as gemlike as those in the third set of 2011 U.S. Open final, winning it was Nadal’s greatest stand yet. The battle in New York was thrilling, but Djokovic hadn’t been at his sharpest, dropping serve three times and making errors at a few key moments. In the fourth set of the Australian Open final, Nadal had just endured the loss of one of the most lopsided sets of his career. He could not produce a single break point, much less a break of serve. And his back had felt the wall at 3-4, love-40. Yet Nadal had won the set anyway. I imagine Nadal was feeling not only elation but immense relief after winning the set; after the hell that had been 2011, he was as lost as he’d ever been, but after this set, I pictured him thinking, Okay, I can do it. I can still beat this guy when he’s playing well. After a full year of dominance from the Serb, Nadal had leveled the matchup. He and Djokovic were equals again.

The fifth set went to a place few matches have ever been. With the match clock ticking close to five hours before it had even started, doubts about Djokovic’s endurance were through the roof. He was stretching uncomfortably as early as the fourth game. Djokovic at 1-2 looks absolutely gassed, Vallejo noted at this point in the match. Limp. Nadal continued his strong play from the fourth set, cruising on serve for a few games. Djokovic’s shots were comparatively flat. Having been so successful at depriving Nadal of time earlier in the match, Djokovic now started to take the ball later, allowing Nadal to crush more forehands. At 2-3 up, Nadal produced a break point for the first time since late in the second set. Djokovic left an inside-out forehand hanging in the middle of the court and Nadal promptly took his chance with a forehand down the line that forced an error. It felt like a nail in Djokovic’s coffin; he had been losing momentum and steam almost since the very beginning of the fifth set.

In fact, Nadal had brought the match back to 2008 or 2009, in a way—he had weathered what seemed to be Djokovic’s best possible patch of play, and he had been rewarded by his opponent’s physical fatigue. Nadal began the 4-2 game by destroying an inside-out forehand winner. Djokovic had hit a backhand that landed smack in the middle of the court, allowing Nadal to feast. The Serb’s shot quality was reeling—it wasn’t that he was consciously imploding, his legs had just fatigued enough to make his previous level of execution impossible. At 30-15, Djokovic approached the net behind a poor inside-out forehand. It was near-suicidal in the face of Nadal’s passing shots, likely the best of anyone ever to play tennis—after so much tennis being played on Djokovic’s terms, the Serb was finally playing Nadal’s game.

The Spaniard ripped a forehand down the line, which Djokovic floated to Nadal’s backhand side with a heavy-handed stretch volley. Racing inside the court, Nadal was presented with an easy putaway. An entire half of the court was open; Djokovic had given up on the ball. It was among the easiest shots of the match.

Waiting for Nadal if he made the backhand: a 4-2, 40-15 lead in the fifth set. A 40-15 lead would essentially clinch him the service game, putting him up 5-2. He’d have a chance to serve for the match at 5-3, and that was if the fatiguing Djokovic could even hold serve first. Even if he did and managed to break Nadal after that, Rafa could still break back at 5-4 to win the match.

But as Nadal himself said at Wimbledon in 2019: “If. If. If. Doesn’t exist.” Nadal sent the backhand an inch wide. Given a window of opportunity at 30-all, Djokovic perked up and reeled off five of the next six games to win the match.

Not that Nadal was reduced to an observer—at 4-all, they played the most torturous rally given the exhausting match that had preceded it, 31 shots of agony that ended with Djokovic sending a backhand miles long and crumpling to the ground in exhaustion. Nadal, by comparison, was barely breathing hard. He never stopped trying, either—down 30-love as Djokovic served for the final at 6-5, he played unbelievable defense to earn one last break point. But down the stretch, Djokovic was able to impose his patterns of play on Nadal ever so slightly more than vice versa.

That said: when Djokovic put the match to bed with a perfectly placed serve and an unreturnable inside-out forehand winner and fell to the ground, this time in ecstasy, Nadal gritted his teeth as if resisting the idea that the match was over, and that, to me, is the defining picture of the final. In 2011, all six of the losses to Djokovic had been over before the final ball was struck. Nadal fought hard, yes, but by the end Djokovic had separated himself in all six matches1. In the 2012 Australian Open final, when Djokovic separated himself, Nadal came back at him, and despite winning the match, Djokovic never fully separated himself again. It was Nadal’s refusal to be left behind that characterized the match more than anything else—not only did he prolong the match from what looked to be a routine four-setter to the insane length of five hours and 53 minutes, but his resistance also pushed Djokovic to greater heights.

And isn’t that what a fighter is, someone defined by the battle, not the result? Nadal’s gritted teeth may have represented anger at the loss, but perhaps more than that, they represented an overriding desire to keep fighting2.

Djokovic had won the match. Nadal had won the story of the match, and the next phase of the rivalry would reward him for it.

That separation came later in some than others, but even in the Miami final, which was decided on a knife’s edge, Djokovic pulled away in the tiebreak to open up a 6-2 lead, which sealed the result.

If this seems like a stretch: when asked in 2015 what his best memory from the Australian Open was, Rafa chose this loss over his win in 2009.

Thanks so much for reading The Golden Rivalry. This chapter was fun to write (this isn’t the best Djokovic-Nadal match, but it may be the most impressive and is my favorite) and challenging (hard to come up with an angle that hasn’t already been done). Hope you liked it. If you’ve been following and enjoying so far, please consider signing up a friend or recommending that they subscribe—by now, you can probably tell that this is aimed at a pretty niche set of readers, and while I’m not concerned with the volume of my readership, I do hope that those who might like this project know about it.

The next official chapter is on the 2012 clay season, but I think a section this important kind of demands an interlude. So I’m going to cook up a bonus feature for Wednesday, then Sunday will be back to regularly scheduled programming. Happy Holidays! -Owen