Chapter 2: Unbreakable Wall

Novak Djokovic played as well as he possibly could have at the 2009 Madrid Masters, and Rafael Nadal still beat him in the semifinal.

The first phase of the Djokovic-Nadal rivalry (at least on clay), then, was a tale of Djokovic playing better and better, yet never quite well enough to take down Nadal at his best. It was a grueling few years; more than once, Djokovic broke himself against the impenetrable wall. If Hamburg 2008 was brutal, Madrid the following year was positively hellish.

Again, Nadal and Djokovic met in the semifinals, and again Federer was waiting in the title round. Nadal, at this point in 2009, was running on fumes. He had won the Australian Open but had to play over nine hours to get through the last two rounds: an exhausting, legendary semifinal with Fernando Verdasco that is to this day the best match I have seen, then a tough, high-quality final with Federer that also went to five sets. He didn’t take much time off afterwards, making the Rotterdam final, then winning Indian Wells, Monte-Carlo, and Rome. (He beat Djokovic in the final of the latter two tournaments.)

By Madrid, his knees were going. He had played way too much tennis. His parents separated in early 2009, which destroyed Rafa’s typically comfortable home life. “Returning back home had always been a joy; now it became uncomfortable and strange,” Nadal wrote in Rafa. “Paradise had become paradise lost.” Unfortunately for Nadal, the physical and mental struggles coincided directly with a fantastic vein of form for his game. Prior to Madrid, Rafa led the ATP rankings with a gargantuan total of 15,360 points. Federer, ranked second, trailed by over 5,000 points. Nadal, likely recognizing that he was where he wanted to be on the court and letting up would jeopardize that, played on.

The semifinal with Djokovic was ominous from the start. The Serb began as he had in Hamburg the previous year, brutalizing forehands and defending well. Nadal was off, so off that it took him until the third set to generate his first break point. Djokovic swept through the first set, and early in the second Nadal took a medical timeout. Had he retired from the match then and there, he likely would have fulfilled more of what was shaping up to be a fantastic season (more on that later), but he continued to play. As he so often had in the past, he survived without playing his best tennis. The second set went to a tiebreak, and at 4-3 up, Nadal set out to attack Djokovic’s backhand.

This is hardly ever a feasible gameplan. Djokovic’s two-hander is a remarkably clean, consistent shot. Even in 2009, well before Djokovic’s best years, it was recognized as a near-impenetrable barrier and an offensive force. Nadal, though, decided to repeatedly scythe wickedly angled forehands to that wing. After a brutal exchange, Nadal drew a loopier shot from Djokovic’s backhand by forcing the Serb onto the stretch, advanced on it, and drilled a winner through the same side of the court. Djokovic was left standing stock-still. All he could do was clap.

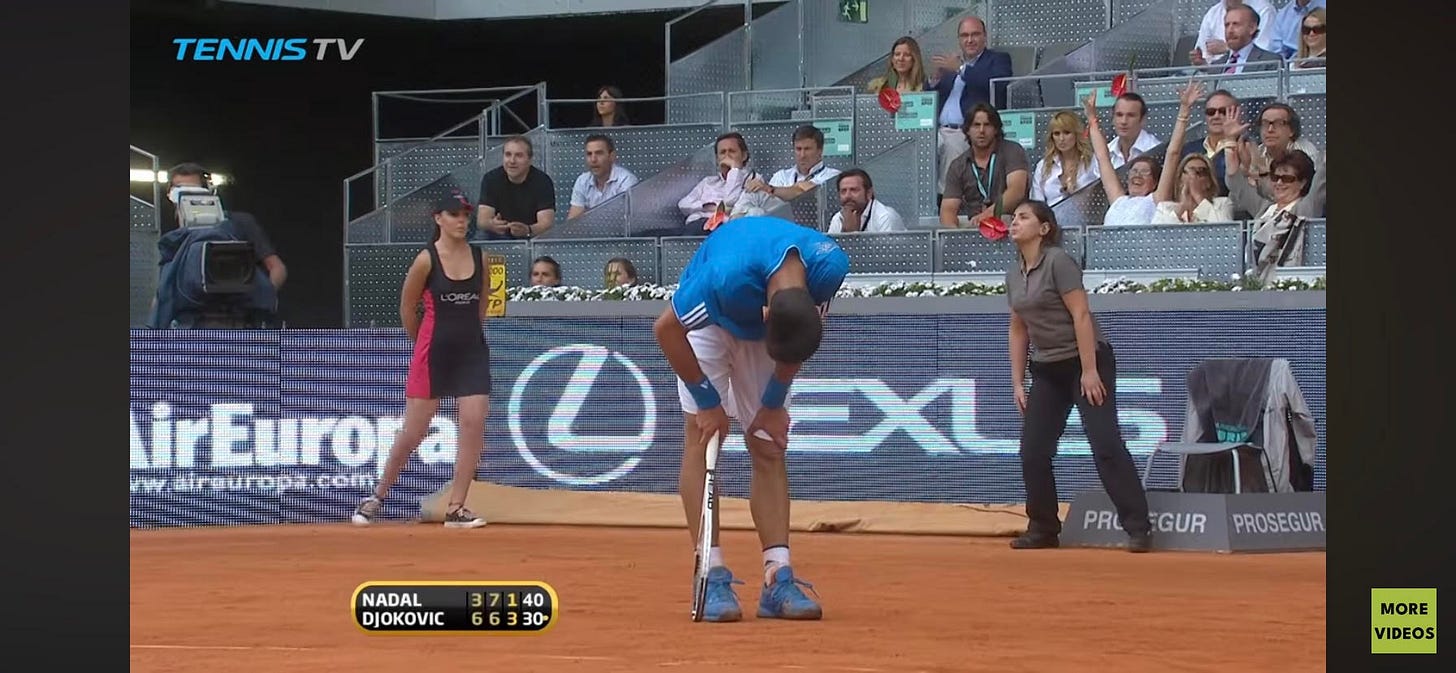

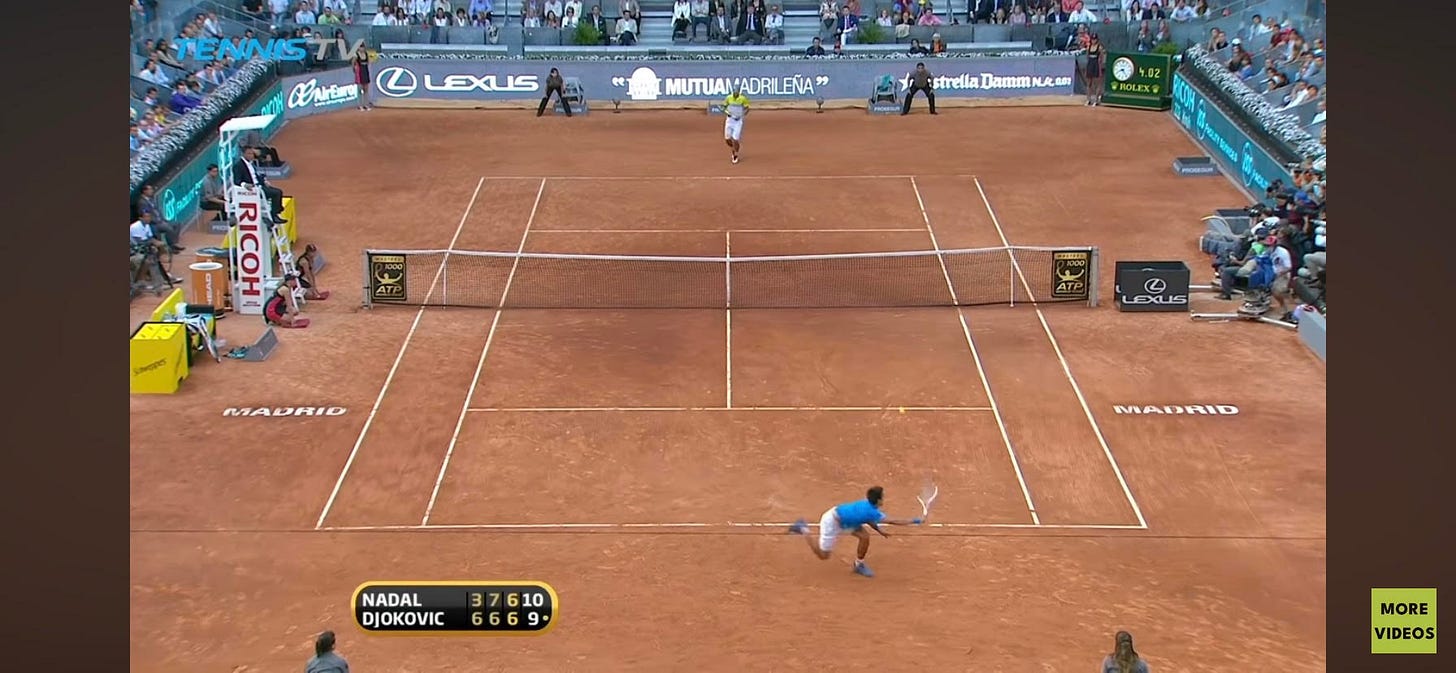

A paradoxical aspect of the Djokovic-Nadal rivalry is that as their matches get longer and therefore more exhausting to the players, so too do the rallies. Common wisdom would suggest that as players fatigue, they would aim to shorten points to avoid putting more strain on their already-waning muscles. But Djokovic and Nadal are incredibly loyal to their high-margin aggression and refuse to hit coin-flip shots unless there really is no other option. With Djokovic leading 3-1, 30-all in the third set of the Madrid semifinal (Nadal had closed out the tiebreak after that wicked succession of forehands), they played a 31-shot rally. It started with Nadal returning a first serve deep, then the Spaniard commenced an onslaught of down-the-line shots from both wings. Djokovic managed to defend well enough to eventually get back to a quasi-neutral position, but Nadal then yanked a fierce backhand crosscourt that Djokovic could only float back short on the ad side. Nadal wrong-footed him with a drop shot winner, and as Djokovic started to run for it, his footwork deteriorated. His arms flailed out as if he had lost his balance. He bent over with his hands on knees for a few seconds afterwards. Failing to recover in time for the ensuing break point, Djokovic missed a forehand, then sank right back into the hands-on-knees position. His legs were shot. The match clock read two hours and 56 minutes; the semifinal would not be over for another hour and seven minutes.

The final set proceeded in that vein, with brutal rally after brutal rally, rallies that didn’t end until one player hit a spectacular winner or bent physically. Fittingly, it came down to a final-set tiebreak. Neither player ever led by more than a point. Djokovic had the first match point, on serve, at 6-5. He got in a good first serve down the middle, which Nadal scraped back into play short on Djokovic’s backhand side. Faced with a quasi-putaway, Djokovic chose to go for a sharp angle rather than a bolt down the line. Nadal read it, sliding into a forehand down the line that was very short, but given that Djokovic had been standing way to the left of the centerline, forced the Serb to run all the way over, depriving him of time to hit another offensive shot. The rally had been evened. They traded blows for another 15 shots, at which point Djokovic looped a crosscourt forehand over the net that landed very centrally but leapt off the court like a bouncy ball. Nadal was waiting in the deuce corner to take on the ball with his forehand, but with the ball bouncing to head-height, no one expected a winner. Yet that was what came. Nadal, reaching over his head to deliver his signature forehand, pulverized an inside-in winner that was placed with such ruthless precision—barely a foot from the line—that Djokovic didn’t run for it.

Djokovic refused to fold after the epic rally, despite how close he had come to winning and despite the Spanish crowd being urged into a frenzy by Nadal’s heroics. At 6-all, he simply bashed the ball all over the court, eventually overwhelming Nadal with sheer pace to draw an errant backhand. During the rally, on consecutive shots, Djokovic had clipped the net cord with an enormous forehand and nailed a backhand down the line right onto the sideline; there was no margin for error anymore. The intent behind every single shot was perfection or bust. At 7-6, Djokovic’s second match point (this one on Nadal’s serve), Nadal survived a good return and proceeded to run his opponent from corner to corner: a fierce backhand crosscourt, a stinging forehand into the other corner, an inside-out forehand back to the ad side. Djokovic, sliding like his life depended on it, survived the barrage to even the rally, much like Nadal had on the first match point.

The crucial shot of the 7-6 point was a strange one—Djokovic hit a moderately deep forehand down the middle, which the Spaniard backhanded short and inside-out. It is best described as a dinky shot. It cleared the net by a few inches. It didn’t appear damaging at all. Its lack of depth proved decisive, though, because its low height over the net forced Djokovic to reach forward and slice a backhand to Nadal’s forehand. The Spaniard’s forehand has unrivaled racket head speed and topspin, so when faced with a slice – many other players are duped by the lack of pace and backspin – Nadal can do whatever he wants with it, his overwhelming topspin easily countering the chipped ball. He ripped an inside-in forehand that Djokovic managed to get back before hastily recovering to the center of the court, but Nadal hit the exact same shot behind the Serb for a winner. Djokovic bent over with his hands on knees for a second, then looked to his box with a despairing smile. Then, as the crowd began to chant Rafa’s name, Djokovic applauded, tapping his racket strings with the heel of one hand.

That wasn’t the end of the match—Djokovic would save a match point of his own, brilliantly drawing Nadal to net with a drop shot before passing him with a forehand. He then had another match point at 9-8, which Nadal saved with his trusty sliding serve out wide (Djokovic barely hit the return long). At 9-all, Djokovic ran around his backhand to hit a forehand return, striking it deep and cleanly and inside-out, but running backwards, Nadal smacked a forehand winner down the line. It was an outrageous shot that no one in their right mind would go for; Nadal was fully airborne when he hit it and barely landed the ball inside the sideline. At 10-9, Nadal’s second match point, he played some great early defense and countered a powerful Djokovic backhand crosscourt with another forehand down the line. It caught Djokovic, who had stepped way inside the baseline to take on the backhand, out of position. He sprinted diagonally as fast as he could and got a swing on the ball, but it was snared by the top of the net. Nadal fell to the ground in ecstasy.

Nadal’s willingness to go for incredibly risky forehands was what had made the difference. His back had been against the wall for virtually the entire match, but when he had to win a point, he looked to his forehand—what would become the greatest weapon ever on a clay court—and trusted it without hesitation or restraint.

If Djokovic was shockingly optimistic after a one-sided loss to Nadal at Roland-Garros in 2006, his quotes after this match appeared to have dented his belief. He had done what he hadn’t been able to at Hamburg the previous year, he had actually met Nadal on that desolate plane where one had to fight like hell for every single point during all three sets, and it still hadn’t been enough. “I played one of my best matches ever,” Djokovic admitted.

We frequently hear Djokovic say that his opponent was the better player when he loses matches nowadays, and while that’s at least partially due to genuine honesty and humility, we all know that part of the reason he allows himself to say that is because he rarely loses at his best and knows all too well that when the rematch comes, he’ll play better and smoke his opponent. A better player on the day, he is saying, but not overall. But here, he had genuinely played his best and lost. To add to the heartbreak, he had won 125 points to Nadal’s 120. His serve had been more effective than Nadal’s, first and second. He had produced and converted more break points. He had led by a set, which he won more easily than either of the sets that Nadal ended up winning. He had three match points. And he had lost. If there was one Djokovic quote to sum up the day, it was this:

“I even played a few points above my limits, and I still didn’t win.”

How do you come back from that? Since 2007, or even earlier, Djokovic’s potential had been obvious. There were no weaknesses in his tennis. He would sometimes wilt physically, but everyone knew that when he put it all together, good things would happen. But against Nadal, he was playing as well as he could, and he was still losing. The 2009 Madrid semifinal was the most extreme manifestation yet, a loss that went beyond Hamburg and the Olympic semifinals—a brutal 6-4, 1-6, 6-4 win for Nadal in which Djokovic missed an overhead on match point. Djokovic had kept physical and mental lapses to a minimum. He played the way he wanted to play. To improve from that, he would have to fundamentally change what he was entirely rather than simply improve the execution of what he was already doing. He was not enough.

I’ll be honest with you, dear reader who’s made it this far: that’s my biggest fear. I’m under no illusions about my flaws, of which there are many. And it’s tempting to use them as excuses for failure. I could be happier if I thought about the past less, or talked to people more, or pitched articles more often. As Rafa once said, “if, if, if, doesn’t exist,” but imagining that “if” really does exist allows me to believe that I’m capable of getting where I want to go. The scenario in which I do everything right and still fall short is terrifying enough to me that far too often, I’ll consciously leave gas in the tank. That lets me maintain fantasies as I fall short of them. This is self-sabotaging, of course—it means I am often a diminished version of myself, and my life lags behind where it should be as a result. I’ve overcome the fear in spots before, and I intend to do a better job of conquering it in the future, but for the most part, it holds power over me and my inability to stand up to it has cost me more than I care to think about.

Plenty of tennis players have had the reckoning I’m so afraid of and been destroyed by it. Verdasco, the valiant runner-up in that glorious 2009 Australian Open semifinal with Nadal, was faced with that same scary truth—he had played the best match of his life and lost. He was unable to take the positives from that match, unable to believe that his best tennis was damn near as good as anyone else’s despite having just proven it, and never reached his best level again.

Djokovic was at a similar crossroads. After losing the Madrid semifinal, his record against Nadal stood at a dismal four wins and 14 losses. And his four wins, at least besides the 2007 Miami quarterfinal, weren’t defining ones. He had never beaten Nadal at a major, or in a final, or on a clay court. He could have continued as he was going indefinitely, beating Nadal on hard courts every so often and savoring those victories, but never taking down the Spaniard when he was at his best. Many players have followed that path.

But Djokovic wanted more. It wasn’t enough for him to be able to live with the best, he wanted to beat the best until he was considered every bit their equal (and eventually, he wanted to surpass them entirely). The Madrid match had slipped through his fingers, but he had felt the strain of what it took to beat Nadal on clay, and he had not broken, he had merely been outdone by the finest of margins. So he was willing to undergo the most painful of self-examinations, ambition outweighing fear. Not immediately—he would spend much of the next year and a half floundering physically and mentally. He had issues with his serve, with his endurance, with his forehand. In the short term, Madrid was more of a roadblock than a stepping stone. Regardless, the signs that Djokovic could one day live with Nadal, anytime and anywhere, were the clearest yet during that fateful 2009 afternoon in the Spanish capital.

Thanks so much for reading The Golden Rivalry. This chapter and the last one have been big ones, and I’d love to exchange thoughts with you about anything in them, whether that’s in the comments or on Twitter. I’ll be back on Sunday with another chapter. -Owen